Ahead of All Parting

It is natural in the grasp of dark winter to turn thoughts toward the darkness, and I have been especially thoughtful about partings and pain recently as several friends wrestle with the iron-cold fates of age and loss and face uncertain futures with a resilience that leans toward Sisyphean strength. Something reminded me of one of the passages of Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus and I began re-reading the remarkable translation by Stephen Mitchell and was staggered by Sonnet XIII which I had not remembered . . . or had simply not been moved by in earlier translations. It is the focus of this post.

Be ahead of all parting, as though it already were

behind you, like the winter that has just gone by.

For among these winters there is one so endlessly winter

that only by wintering through it all will your heart survive.

Be forever dead in Eurydice-more gladly arise

into the seamless life proclaimed in your song.

Here, in the realm of decline, among momentary days,

be the crystal cup that shattered even as it rang.

Be-and yet know the great void where all things begin,

the infinite source of your own most intense vibration,

so that, this once, you may give it your perfect assent.

To all that is used-up, and to all the muffled and dumb

creatures in the world's full reserve, the unsayable sums,

joyfully add yourself, and cancel the count.

This translation by Stephen Mitchell can be found at PoemHunter: http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-sonnets-to-orpheus-book-2-xiii/

The haunting line, “Be forever dead in Eurydice” refers to the myth of Orpheus, the greatest musician in all Greece, and his beloved bride, Eurydice. Within a short time after their marriage Eurydice is bitten by a snake and dies. Orpheus in his grief sacks the walls of Hades to plead for her release. As the Bullfinch version tells us:

As he sang these tender strains, the very ghosts shed tears. Tantalus, in spite of his thirst, stopped for a moment his efforts for water, Ixion's wheel stood still, the vulture ceased to tear the giant's liver, the daughters of Danaus rested from their task of drawing water in a sieve, and Sisyphus sat on his rock to listen. Then for the first time, it is said, the cheeks of the Furies were wet with tears. Proserpine could not resist, and Pluto himself gave way. Eurydice was called. She came from among the new-arrived ghosts, limping with her wounded foot. Orpheus was permitted to take her away with him on one condition: that he should not turn round to look at her till they should have reached the upper air. Under this condition they proceeded on their way, he leading, she following, through passages dark and steep, in total silence, till they had nearly reached the outlet into the cheerful upper world, when Orpheus, in a moment of forgetfulness, to assure himself that she was still following, cast a glance behind him, when instantly she was borne away. Stretching out their arms to embrace one another they grasped only the air. Dying now a second time she yet cannot reproach her husband, for how can she blame his impatience to behold her? "Farewell," she said, "a last farewell," and was hurried away, so fast that the sound hardly reached his ears.

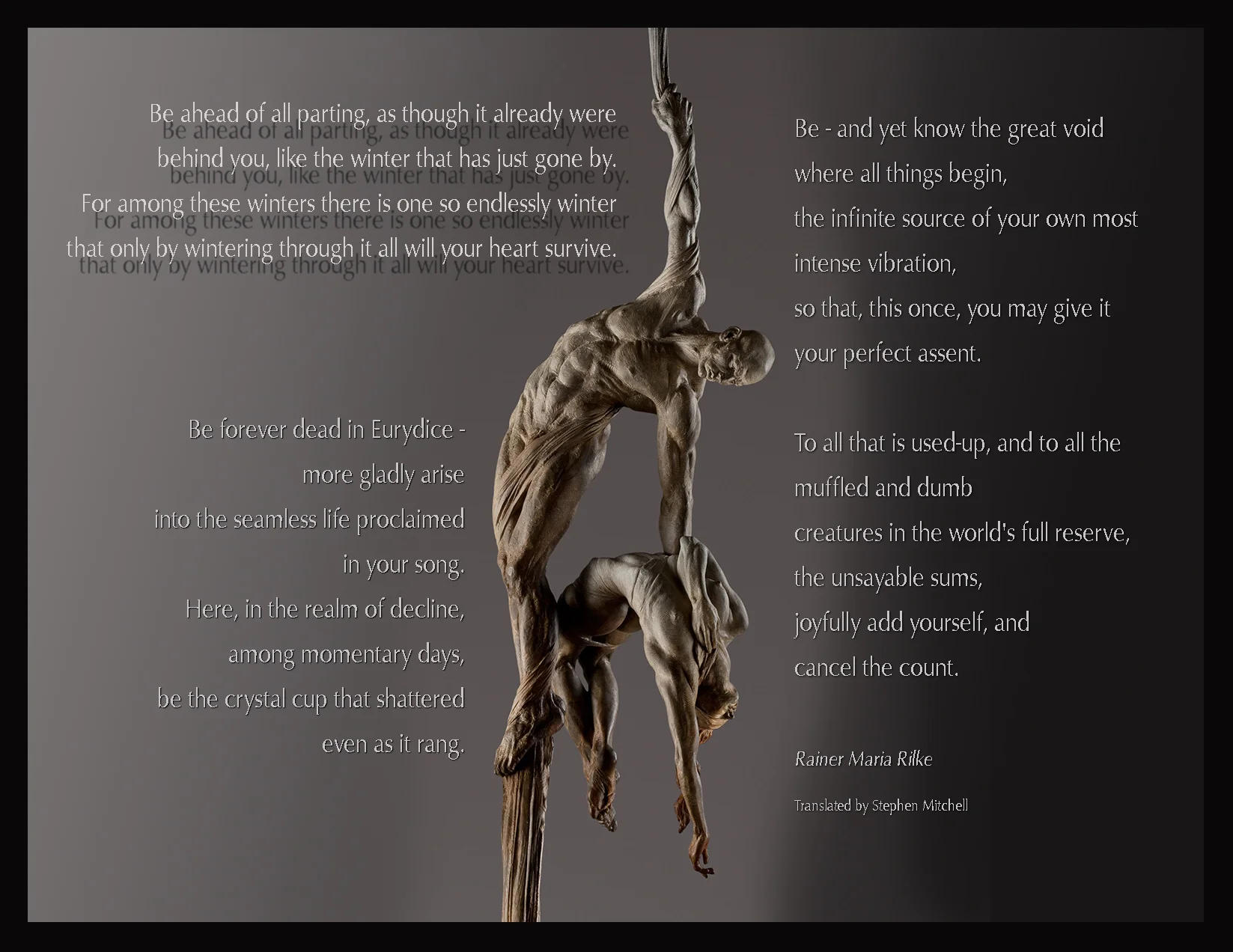

This moment of utmost pathos has found its way for hundreds of years into songs, paintings, dances, opera and sculpture. I had not imagined that any image could do justice to the poem that Rilke fashioned around this scene, but I stumbled upon a contemporary sculpture by Richard MacDonald and recognized a work of art on a par with Auguste Rodin for its sublime majesty of human expression.

http://www.richardmacdonald.com

In this image I feel the twin desires of the human heart: to hold fast to that which is the beloved object, and to surrender to the greater power – whether that be Love, God or Death. In this single image both great longings are born aloft in unbearable tension with such tenderness that one weeps for all humanity – constantly torn by these irreconcilable forces.

But Rilke goes beyond the pathos of death and loss to look death straight in the face and give the remarkable advice: “Be ahead of all parting.” Like the shamans who wear symbols of death always on their bodies, we are reminded that living in this world is easier if we reach out to plant one imaginal foot in the other world. As Don Juan advised Carlos Castaneda about following the path with heart:

A warrior considers himself already dead, so there is nothing to lose. The worst has already happened to him, therefore he's clear and calm; judging him by his acts or by his words, one would never suspect that he has witnessed everything.

Carlos Castaneda from Tales of Power

Seven years before this poem was written, Rilke had penned a letter to a correspondent that strikes me as one of the most illuminating commentaries ever written on God and death. In many ways it is the perfect companion to C.G. Jung's book, Answer to Job, which was written in 1952. For those of you who have read this book, which Jung declared was the only piece of writing that he ever did which he would not alter in any way, the following passage from Rilke almost sounds like the query to which Answer to Job is the reply! It is a lengthy morsel, but worth every pixel.

Let us agree that from his earliest beginnings man has created gods in whom just the deadly and menacing and destructive and terrifying elements in life were contained – it's violence, it's fury, it's impersonal bewilderment – all tied together into one thick knot of malevolence: something alien to us, if you wish, but something which let us admit that we were aware of it, endured it, even acknowledged it for the sake of a sure, mysterious relationship and inclusion in it.

For we were this to; only we didn't know what to do with this side of our experience; it was too large, too dangerous, too many-sided, it grew above and beyond us into an excess of meaning. We found it impossible – what with the many demands of the life adapted to habit and achievement – to deal with these unwieldy and ungraspable forces; and so we agreed to place them outside us. But since they were an overflow of our own being, its most powerful element, indeed were too powerful, were huge, violent, incomprehensible, often monstrous – how could they not, concentrated in one place, exert an influence and ascendancy over us? And remember, from the outside now. Couldn't the history of God be treated as an almost never-explored area of the human soul, one that has always been postponed, saved, and finally neglected?

And then, you see, the same thing happened with death. Experienced, yet not to be fully experienced by us in its reality, continually overshadowing us yet never truly acknowledged, forever violating and surpassing the meaning of life – it too was banished and expelled, so that it might not constantly interrupt us in the search for meaning. Death - which is probably so close to us that the distance between it and the life-center inside us cannot be measured - now became something external, held farther away from us every day, a presence that worked somewhere in the void, ready to pounce upon this person or that it its evil choice. More and more, the suspicion grew up against death that it was the contradiction, the adversary, the invisible opposite in the air, the force that makes all our joys wither, the perilous glass of our happiness, out of which we may be spilled it any moment.

All this might still have made a kind of sense if we had been able to keep God and death at a distance, as mere ideas in the realm of the mind. But Nature knew nothing of this banishment that we had somehow accomplished – when a tree blossoms, death as well as life blossoms in it, and the field is full of death, which from its reclining face since forth a rich expression of life, and the animals move patiently from one to the other – and everywhere around us, death is at home, and it watches us out of the cracks in Things, and a rusty nail that sticks out of a plank somewhere, does nothing day and night except rejoice over death.

~ Rilke, in a letter to Lotte Hepner, November 8, 1915

This passage foretells the poem in its suggestion that what we think of as death is as close to us as life itself; that it is the other side of the moon only, as present in the field of flowers as the life whose beauty we extol. To embrace the monstrous and own it, to take back the shadow side of the bright gods we have made, is the very task that both Jung and Joseph Campbell have called the supreme task of our age. Here it is stated with visionary power a generation earlier.

Be forever dead in Eurydice - more gladly arise

into the seamless life proclaimed in your song.

For those who are already fans of Rilke, it may interest you to hear how he felt about this particular poem. In a letter written to a friend a couple of months after the epiphany of February 1922, in which he completed all of the Duino Elegies and the entire cycle of the Sonnets to Orpheus, he said:

"The thirteenth sonnet of the second part is for me the most valid of all. It includes all the others, and it expresses that which - though it still far exceeds me - my purest, most final achievement would someday, in the midst of life, have to be."

(Letter to Katharina Kippenberg, April 2, 1922)

So, dear friends, however you will “winter through it” in these next few months, I hope this poem will walk beside you like a soulful accompaniment, like Orpheus with his lyre walking among the shadows.

~ Rebecca