Reflections on the Mythopoetic

by Rebecca Armstrong

“The principal method of mythology is the poetic, that of analogy; in the words of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, it is ‘the representation of a reality on a certain level of reference by a corresponding reality on another: death by sleep, for example,… the light of the sun as of consciousness; the darkness of caves or of the ocean depth as of death or of the womb; the waning and waxing moon as a sign celestial of death and rebirth; and the serpent’s sloughing of its skin as an earthly sign with the same sense.” (Joseph Campbell, Historical Atlas, Vol 1:1, p.9)

The Joseph Campbell Foundation proclaimed its mission boldly at its inception back in 1990 with the intriguing phrase: “a not-for-profit organization seeking to formulate a mythopoetic response to contemporary literalism and cultural retrenchment.” This deliciously difficult phrase holds what is, in many ways, the clue to what Campbell’s work is all about. As Mrs. Joseph Campbell (Jean Erdman) reminded me several years ago – “The real mission is to remind people that myths are not lies, but deepest truth!” In order to comprehend the deep truth of mythology one must be able to grasp the meaning of metaphor which leads immediately into the mythopoetic view of the world.

Both the method and the meaning of myth are deeply dependent on a view of the world called the mythopoetic, a term borrowed directly from the Greeks [muthopoiein, to relate a story : muthos, story + poiein, to make.] The term has been used by Robert Bly and consequently the men's movement here in America, and is now popularized in numerous literary and critical essays. (For instance, a recent book by Leonard Wessell with the unlikely title, Romantic Irony and the Proletariat: the Mythopoetic Origins of Marxism, bespeaks the extent to which the term is now "in.")

What is significant about this worldview is that it attributes to the storyteller a creative power not normally awarded this activity. It is related to the term 'imaginal' which was coined by French orientalist, Henri Corbin, to describe a particular state of consciousness sought by the mystics of ancient Persia, but later became a much-used term in the post-Jungian archetypal psychology movement. A traditional discussion views a mythology as reflecting the values of the status quo in relation to the dominant culture, and imagination as being outside of or beyond the bounds of reality. But, as theologian and mythologist David Miller suggests, "a mythopoetic reimagining of a mythology reverses this oppressive function by offering an iconoclastic critique of existing social and political norms. In postmodern mythological theory, a question is raised as to whether all so-called “mythology” is in fact “mythopoesis.” (from Miller’s class syllabus for Pacifica Graduate Institute)

For the large class of Americans dubbed "the cultural creatives" religion is being seen as a form of mythology, that is, as a potent story for meaning-making and value-formation, but not as Truth, in the former understanding of that word; not as a once-revealed doctrine of sacrosanct, normative reality against which one's own vision of truth is not only meaningless, but potentially dangerous, but as an essentially co-creative activity of spiritual growth. For this group of people the notion of a mythopoetic attitude towards the world is 'the beginning of wisdom.' The poet and best-selling author, David Whyte, sums up the collective yearning in mythopoetic terms:

"I think the tremendous thirst we experienced around Joseph Campbell's work was a sudden remembrance of the great story in which we're all involved. But the question remains, can you tell it? Can you tell it in such a way that you know your place in the story?" [David Whyte, interview published in Magical Blend]

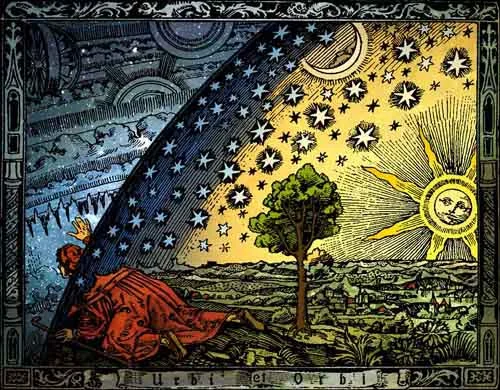

The telling of the tale, however, is not one of words, but of images, for as both Campbell and archetypal psychologists remind us, the soul’s language is that of imagery. Perhaps the most succinct definition of the mythopoetic method is that given by James Hillman in A Blue Fire:

“We amplify an image by means of myth not in order to find its archetypal meaning but in order to feed it with further images that increase its volume and depth and release its fecundity.” (p. 60)

Campbell’s approach was a neat inversion of the first clause, that is to ‘amplify a myth by means of an image’, something which he did with greater precision and passion than any mythographer before or since, and which enabled him to grasp the inner psychological similarities between apparently divergent mythic stories by seeing the mythic memes undergirding them. (See The Mythic Image and all volumes of The Historical Atlas for more on imagery in myth.)

And now, to bring this subject back to mythology and its mystical function, one must ask -- what are we doing to promote a mythopoetic response to literalism? Against the inebriating numbness of computerized, virtual reality, where the only eye looking at you is the reflection of your own intoxication in the flickering screen, what can we do to release the Thou, the soul in the world, so that our sense of mystery is restored? What can we do to teach sacred technologies that inspire the 'gazing and sighing' that unites our heart with the soul of the world, as the troubadours' hearts were linked to their beloveds'?

The new charge placed upon thinkers of this millennium is that we must use the tools of the mythopoetic imagination, within the limits of reason and modern, scientific cosmology, to make possible the feelings of awe and wonder that make it a "reasonable proposition" to overcome Nietzschean nihilism and get out of bed in the morning.

This is no small task, but it is clearly the one function of a living mythology which must be addressed by artists and poets and ‘cultural creatives,’ for no one else is capable of making sense of it. It is this challenge which must be taken up if the mythic dimension of the seen world is to become metaphorically capable of rendering spiritual life tangible – becoming transparent to transcendence in fulfillment of the first function of a living mythology.

[An earlier version of this essay first appeared in 2003 as one of the "Monthly Myth Letters" on the website of the Joseph Campbell Foundation.]